If you can’t put an antenna outside, the attic starts looking real tempting. It’s out of the weather, out of sight for the neighbors and the HOA patrol, and it still gets you on the air. But here’s the catch. Your roof is not RF-transparent, and the stuff between your antenna and the sky matters way more than most people think. If you understand what you’re losing (and why), you’ll make better choices about where to hang the wire, what to expect on the air, and whether the attic install is worth crawling around up there for in the first place.

📌 TL;DR — Attic antennas work, but with tradeoffs

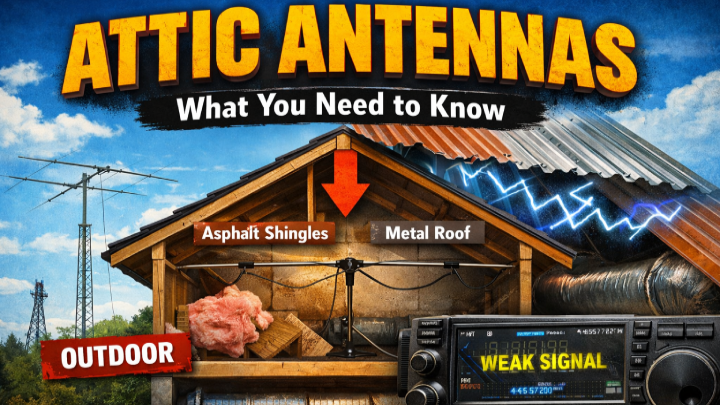

- Signal loss: Expect 3-6 dB with asphalt shingles, 8-11 dB with tile, 20+ dB with metal roofs.

- Real-world impact: That loss translates to reduced range, weaker receive, and fewer contacts on marginal bands.

- Key factors: Roof material, attic clutter (ductwork, wiring), antenna height above floor, and building construction all matter.

- Who it's for: Hams with restrictive covenants, renters, or anyone who needs stealth over maximum performance.

The question isn’t whether attic antennas work. They do. The real question is how much you’re giving up, what’s causing it, and what you can realistically do about it. If you’re thinking about an attic dipole (or you already have one strung up and you’re wondering why it feels “meh”), this is the breakdown: the numbers, the materials, and what it looks like in the real world when RF has to punch through your roof.

Why attic antennas are popular (and when they make sense)

Attic antennas exist because compromise is basically baked into amateur radio. Not everybody has the space, the trees, the tolerant neighbors, or an HOA that won’t lose their mind over a piece of wire. For a lot of hams, the attic is the only place you can get a full-size horizontal antenna up without turning it into a neighborhood argument.

And honestly, the appeal is obvious. You’re indoors. No weatherproofing, no ice loading, no wind trying to turn your dipole into spaghetti. You don’t have to explain to anyone why there’s a wire between two trees, and you don’t have to climb a ladder in the dark to fix something after a storm.

It’s also easier to experiment. Want to change the feedpoint? Adjust the length? Move the thing a few feet? You can do that without dragging out ropes and a slingshot. You’re up there in a dusty attic, sure, but you’re not fighting the weather.

But there’s a cost. And you feel it on the air.

The roof above you isn’t just sitting there being polite. It’s absorbing some of your signal, reflecting some of it back down, and scattering the rest. Depending on what that roof is made of, the loss can be “okay, I can live with this” or “why did I even bother.”

Then there’s the part people gloss over. Attics are noisy and full of junk that messes with antennas. You’ve got wiring everywhere, big metal HVAC ducts that act like reflectors, plumbing vents, and sometimes foil-backed insulation that basically turns the whole space into a low-budget Faraday cage. Once the antenna is up, all that stuff affects it in ways that are annoying to predict and harder to fix after you’ve already strung the wire.

So when does an attic antenna make sense? When the goal is getting on the air, not winning a contest weekend. When you’re stuck with restrictions. When you’re running CW or digital and you don’t mind being down a few dB. And when you’re honest with yourself going in. This is a compromise setup, not a stealth superstation.

Understanding signal loss: what the numbers actually mean

People throw around signal loss numbers like everyone automatically understands what 3 dB or 10 dB feels like in real life. Most people don’t. So let’s keep it simple.

Every 3 dB of loss cuts your effective radiated power in half. That’s not “sort of.” That’s literally how the math works.

So if you’re running 100 watts into an outdoor dipole and you move that same dipole into the attic under asphalt shingles, you’re looking at around 3 to 6 dB of loss depending on the roof and what’s in the attic. At 3 dB, your 100 watts behaves like 50 watts outside. At 6 dB, you’re down to 25 watts. You’ll still make contacts. But you’ve dropped about one to two S-units on the other end, and that’s the difference between “good copy” and “say again?”

With tile roofs, the loss climbs to 8 to 11 dB. Now your 100 watts is acting like a 10 to 15 watt rig outdoors. That’s where things start to sting. Contacts that were easy become marginal. Stations that used to hear you clean now only catch pieces. And on bands where conditions are already weak, you’re basically playing the game on hard mode.

Metal roofs are where it gets ugly fast. At 20+ dB of loss, your 100 watts is functionally behaving like 1 watt or less making it outside. That’s not “a little compromise,” that’s a full-on handicap. At that point you’re not running a great antenna, you’re feeding a dummy load that occasionally gets lucky when propagation is perfect and the other station has serious ears.

The reason we even have these numbers is because the TV antenna world has done a ton of controlled attic-vs-rooftop testing. Companies like Channel Master and Antennas Direct have published measured results comparing identical antennas indoors and outdoors. Their tests were mostly VHF and UHF, but the basic physics still applies to HF. HF can do a little better thanks to longer wavelengths, but the losses from the materials are still real.

And one more thing people forget. These losses stack.

If you’re already running a compromised antenna, short for the band, poorly matched, installed near metal, or tuned with a “good enough” mindset, you’re piling losses on top of losses. The roof is the obvious one, but it’s not the only thing dragging your signal down.

Roofing materials: what you're actually transmitting through

The roof over your head decides whether an attic antenna is a workable compromise or a waste of time. Here’s what the published data and real-world ham experience says about common roofing materials and how badly they beat up your signal.

Asphalt shingles: the best-case scenario

Standard asphalt shingles are about as RF-friendly as roofing gets. They’re non-conductive and relatively thin. They still absorb some signal, but the loss is manageable. Testing puts the attenuation at around 3 to 6 dB for most installs, and that lines up with what most hams report when they compare attic to outdoor.

That 3 to 6 dB range isn’t a promise. It’s an average. The real loss depends on shingle thickness, how much tar and aggregate is in the mix, whether there’s ice-and-water shield underneath, and how wet everything is. Wet roofing absorbs more RF than dry. You’ll notice performance shifts after heavy rain, and it’s not in your head.

If you’ve got asphalt shingles and a fairly clear attic, you’re in the best attic-antenna scenario there is. You’ll still lose signal compared to being outside, but it’s workable. Especially on the lower HF bands where being down a couple S-units doesn’t automatically kill the QSO.

Clay and concrete tiles: where loss starts to hurt

Tile roofs look great and last forever, but they’re brutal for RF. Clay tile, concrete tile, slate, they all share the same problem. They’re thick, dense, and lossy. Published testing shows 8 to 11 dB of reduction, and in the real world it can be worse depending on how thick the tiles are and how much moisture they’re holding.

At 8 to 11 dB, you’re giving up most of your effective power. Your 100 watt rig is now acting like a 10 watt rig outdoors. You can still make it work, especially with CW and digital, but don’t pretend it’s the same as being outside. It isn’t.

Tile also messes with patterns. It’s not just attenuation. Thick roofing materials can distort where the antenna wants to radiate, and you’ll see weird “this direction is great and that direction is dead” behavior that has nothing to do with geography and everything to do with what the roof is doing to your RF.

Metal roofs: the antenna killer

Metal roofs are where attic antennas go to die. Standing seam steel, corrugated metal, metal shingles, it doesn’t matter. The result is the same. 20+ dB of loss, and that’s the optimistic version. In a lot of cases, the antenna is basically useless for anything beyond strong local groundwave.

The problem isn’t just absorption. Metal reflects RF. When your antenna is under a big conductive plane, a lot of your signal never makes it out of the attic. It bounces back down, sets up standing waves, and turns the attic into an RF funhouse.

You’ll hear the occasional story of someone who “made it work” under a metal roof because of seams or gaps that let some signal leak out. Sure, it happens. But counting on that is like counting on a damaged coax run to perform because the shield isn’t totally shorted. It might work today. It’s still not a plan.

If you’ve got a metal roof and attic mounting is your only option, set your expectations low. You’re not building a compromise station. You’re building something that will work on the best days, and frustrate you the rest of the time.

Specialty materials and modern construction

Modern construction adds a whole extra layer of pain. Radiant barriers, foil-faced insulation, reflective roof coatings, all that stuff is designed to reflect energy so your attic doesn’t cook you in the summer. Unfortunately, it reflects RF too. It doesn’t care what kind of energy it is.

Foil-backed insulation is especially nasty. It acts like a reflective layer between your antenna and the outside world. It’s not quite as destructive as a solid metal roof, but it’s bad enough that your performance can drop hard even if your shingles are asphalt. If you’ve got foil on the rafters or attic walls, assume extra loss beyond what the roof material itself would cause.

Solar panels can make things even weirder. They’re mounted on top of the roof, not in the attic, but they still introduce conductive surfaces, metal frames, and a bunch of wiring that can interact with the antenna pattern. There isn’t a ton of published testing yet, but real-world reports point in the same direction. If the panels cover a big chunk of the roof right above the antenna, the attic setup takes another hit.

Beyond the roof: other factors that affect attic antenna performance

The roof gets all the attention, but it’s not the only thing messing with your attic antenna. Attics are full of metal. And every bit of it wants to interact with your dipole whether you asked for it or not.

HVAC ductwork and plumbing

Most attics have ductwork running through them, and metal ducts act like unintentional reflectors. If your dipole runs parallel to a big duct, you’ve basically built a parasitic element you can’t tune out. If the duct runs perpendicular, it absorbs and redirects energy that should’ve been radiating into the sky.

Plumbing vents, copper water lines, and stacks aren’t as bad as ductwork, but they still matter. The more metal you’ve got up there, the more your radiation pattern gets warped. That’s why two hams can run the same antenna under the same roofing material and get totally different results. One attic is clean. The other is full of infrastructure.

Electrical wiring and RF noise

Your attic has wiring everywhere, and it’s not always friendly to HF. Modern houses are full of noise sources. LED dimmers, cheap wall-wart power supplies, smart switches, even certain appliances, they all love to spray hash across the bands.

The wiring itself isn’t the main problem unless you run the antenna right on top of it. The bigger issue is the devices at the end of those wires. If you’re hearing S9 noise, start flipping breakers one at a time and see what drops out. Sometimes it’s your own house and you can fix it. Sometimes it’s the neighbor’s solar inverter, and that’s where the fun ends.

Antenna height and placement

Height matters even in an attic. A horizontal dipole’s pattern changes based on how high it is above ground. In an attic, you’re rarely as high as you think you are, and that affects your takeoff angle.

Lower antennas favor higher takeoff angles. That’s great for NVIS and regional work, and it’s lousy for DX. If you’re trying to work Europe from the U.S. with an attic dipole 25 feet off the ground, you’re fighting both roof loss and geometry. An outdoor antenna at the same height would absolutely work better, but even that still wouldn’t be “ideal” for long-haul DX.

Placement in the attic matters too. Antennas near gable ends can sometimes do better than antennas buried in the center, especially if that gable is pointed in the direction you’re trying to work. It’s not magic. It’s just one more little edge you can grab when you’re already giving up performance by being indoors.

Real-world operator experiences: what actually happens

Published data is great for understanding the theory, but ham radio is always about the real world. And in the real world, attic antennas work. They just come with limitations you can’t pretend away.

If you’ve got asphalt shingles and a fairly clean attic, the results can be surprisingly decent, especially on 40 and 80 meters. Guys I know run attic dipoles and make DX contacts, run digital all day, and have plenty of fun. The loss is there, but smart operating makes up for a lot. Pick better times, use modes that handle weak signals, and accept that you’re not going to win every pileup.

Move into tile roof territory and the story changes. Local and regional contacts stay easy, but DX gets noticeably harder. Marginal bands get even more marginal. The stuff you used to work without thinking becomes something you work only on the good days.

Metal roof operators have it the worst. Some report their attic antennas are basically dead except for the strongest locals. Others find a band or two that works better than expected, but it’s not consistent. The overall consensus is simple. Metal roofs and attic antennas don’t mix. If that’s your situation, you’re better off finding any outdoor option you can, even if it’s a compromised vertical or a temporary setup.

One thing that comes up over and over: tiny changes matter. Move the antenna a few feet. Rotate it. Get it away from a duct. Performance can shift a lot. That makes attic antennas more finicky than outdoor installs, but it also means you can improve things with a little experimenting instead of just accepting defeat.

Making the decision: attic or outdoor?

Sometimes you don’t get a choice. Outdoor isn’t allowed, and the attic is the only place you can hang wire. If that’s you, stop stressing and put the antenna up. Being on the air with a compromise antenna beats being off the air with the perfect plan.

But if you do have options, this is easy. If you can go outside, go outside. Even a low outdoor wire will outperform an attic dipole under tile, and it will absolutely smoke one under a metal roof. The difference isn’t subtle. It’s the difference between working a pileup and just listening to it.

If outdoor isn’t possible and your roof is asphalt shingles, an attic dipole is a solid choice. You’ll lose signal, but you’ll still make contacts. On lower bands especially, the performance hit is something you can work around. Lean into CW and digital, operate when conditions favor you, and don’t expect to compete with stations running big outdoor beams.

If you’re under tile, you’re deep in compromise territory. You can still make it work, but don’t lie to yourself about what it is. DX gets harder. You’ll spend more time listening than transmitting on some bands. But if the alternative is no radio at all, it’s still worth doing.

If you’ve got a metal roof, exhaust every other option first. Outdoor verticals, mobile setups, a temporary wire you toss up when you operate, even a field setup down the street. Anything that gets you out from under that metal. An attic antenna under a metal roof is a last resort, not a starting point.

Tips for maximizing attic antenna performance

If you’re committed to an attic install, you can absolutely squeeze more performance out of it. You just have to treat it like what it is: a weird, compromised environment that needs a little extra attention.

Get the antenna as high as possible

Get it up near the peak. Every inch helps. If you’ve got the choice between hanging it low over the joists or getting it closer to the roofline, go higher. The change in takeoff angle and losses can be bigger than you’d think.

Keep it away from metal

Before you string anything, take five minutes and look around up there. Figure out where the ductwork runs, where electrical wiring bunches up, where the plumbing vents are. Then keep your antenna as far from all of it as you can. You don’t have to make it perfect, but don’t run the dipole right alongside a giant metal duct and then act surprised when the pattern looks weird.

Experiment with orientation

A dipole has nulls off the ends and maximum radiation broadside. Outdoors, you can predict that pretty well. In an attic full of metal and reflective materials, the pattern gets distorted. The direction that should work on paper isn’t always the direction that works on the air. So try it. Rotate it if you can. Move it a few feet. See what actually changes in your signal reports.

Use an antenna analyzer

Resonance in an attic is not the same as resonance outside. Nearby metal and the cramped environment change the antenna’s electrical length. So measure SWR and resonance with the antenna installed, not on a bench. A few inches of wire adjustment can move resonance a lot, and what was perfect outdoors might need retuning once it’s up in the attic.

Consider lower bands

Lower HF bands are where attic antennas feel the least painful. Material losses tend to be less severe at lower frequencies. An 80-meter dipole under asphalt shingles can be surprisingly usable compared to an outdoor antenna. A 20-meter dipole under the same roof will feel more “held back.” If your interests lean toward 80 and 40, attic installs make more sense.

Embrace digital modes

Digital modes are a cheat code for compromised antennas. FT8, FT4, and other WSJT modes work extremely well with attic antennas because they can decode signals that would be frustrating on SSB. You’ll make contacts you’d never get by voice, and you’ll hang with stations that have way better antennas. And no, the computer doesn’t care that you’re 6 dB down. It’ll still decode you.

The bottom line on attic antennas

Look, attic antennas are a compromise. Everybody knows that. But they’re not a joke, and they’re not “fake ham radio” either. If you understand what you’re up against and you do a decent job with placement and tuning, you’ll get on the air and you’ll make contacts. That’s the whole point.

- Asphalt shingles: 3-6 dB loss, very workable for most operating

- Tile roofs: 8-11 dB loss, challenging but viable with the right modes

- Metal roofs: 20+ dB loss, explore other options first

- Attic clutter, electrical noise, and antenna placement all affect performance beyond just roofing material

- Lower bands and digital modes are where attic antennas shine most

If you can go outside, do it. If you can’t, don’t let that stop you. Put a dipole in the attic, keep it high, keep it away from metal, tune it properly, and get on the air. You’ll be surprised what you can work when conditions are decent and you’ve got your station dialed in.