If you hang around hams for more than five minutes, you will hear the words "ground plane," "radials," and "counterpoise" tossed around like everybody learned them in kindergarten. New operators quickly realize that all three are some kind of "ground," but what each one does and how they affect antenna performance is rarely explained clearly. This guide breaks those ideas down so you can look at a vertical, mobile whip, or end fed wire and immediately understand what the RF is actually pushing against.

📌 TL;DR — What "ground" really means for your antenna

- Core idea: Ground planes, radials, and counterpoises all give current a return path so the antenna can radiate efficiently.

- Why it matters: A poor RF ground hurts efficiency, changes SWR, and can send RF back into the shack.

- Key benefit: Matching the right style of "ground" to the antenna type improves signal, pattern, and noise pickup.

- Who it’s for: New and intermediate hams who want their verticals, mobiles, and end fed wires to actually play well.

The first big point: RF "ground" is not the same thing as electrical safety ground. Your station still needs proper bonding and lightning protection, but the antenna itself just needs a solid RF return path so current has somewhere to go. That return path might be the earth under a vertical, the metal roof of a car, or a single wire hanging off the back of an end fed matchbox.

When that return path is small, resistive, or in the wrong place, the antenna system starts doing weird things. SWR shifts, the pattern tilts, the coax shield starts radiating, and sometimes the microphone bites you. When the RF ground is large, low loss, and where the designer assumed it would be, the same antenna suddenly sounds like a different radio.

Quick definitions: ground plane, radials, and counterpoise

Before we look at specific antennas, it helps to pin down the language. All three terms describe the "other half" of the antenna - the part that lets current leave the feed point, create an electric field, and then return. The physical implementations look different, but the physics is the same.

How RF ground affects real world performance

| Metric |

Value |

Why It Matters |

| Radiation efficiency |

Can swing by 10 dB or more between poor and good RF ground |

Directly affects how loud you are on the other end of the contact. |

| Takeoff angle |

Changes with radial layout and soil under a vertical |

Controls whether your signal goes mostly local, DX, or somewhere in between. |

How these concepts map to common antenna types

Every antenna you build or buy assumes something is acting as the "other half." Once you learn to spot that part of the system, tuning gets easier, troubleshooting makes more sense, and you will get a lot more out of the same piece of aluminum or wire.

- Step 1: Identify where current leaves and returns to the feed point. On a vertical, that is usually the base or mount.

- Step 2: Decide what is providing the RF return. Is it soil, a metal surface, radials, or a single counterpoise wire?

- Step 3: Check whether that return path is big enough, low loss enough, and placed where the designer expected it.

Ground planes vs radials vs counterpoise at a glance

Hams often use these three words interchangeably, but they are usually describing slightly different things. The easiest way to keep them straight is to look at how "infinite" the return path is and how it is physically arranged around the feed point. From there, you can decide what makes sense for your own station layout.

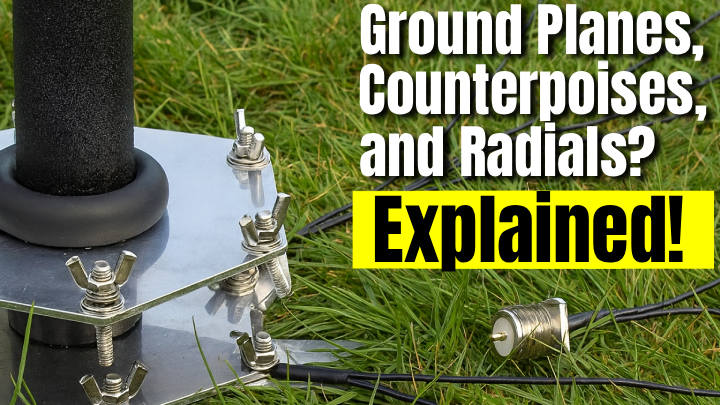

- Ground plane: A reasonably large conductive surface that behaves like part of an infinite sheet. Think car roof, tower top plate, or a metal balcony.

- Radials: Individual wires fanned out from the base of a vertical that approximate a ground plane. They can be buried or elevated.

- Counterpoise: A deliberately sized wire or network of wires that completes the RF circuit when you cannot get a real ground or radial field.

How RF current really flows in these systems

Picture a basic quarter wave vertical. On transmit, current flows up the radiator, charges the space around it, and then flows back down through the earth or radial system to the feed point. If that return path is small or resistive, some of your power just turns into heat. If the return path is big and low loss, more power turns into a clean RF field and less ends up warming the dirt.

The same idea applies to an end fed half wave. The long wire does most of the radiating, but current still has to return to the matchbox. If there is no proper counterpoise, the coax shield becomes that return. Suddenly your feed line radiates, your pattern gets weird, and the shack starts to feel "hot" with RF. Adding a short counterpoise wire and a choke at the right spot gives that current a better path and calms everything down.

What a "ground plane" really is

A ground plane is any conductive surface big enough and close enough to the antenna to act like a mirror for RF. The perfect ground plane is an infinite, perfectly conducting sheet. In the real world, we use things like vehicle bodies, metal roofs, and top plates on towers. For a quarter wave whip on VHF or UHF, the car roof is so large compared to the wavelength that it behaves very close to that ideal.

When a vertical is designed for a ground plane, the radiation pattern assumes that giant mirror. The pattern is usually low angle and fairly clean. If you move that same whip to a tiny magnetic mount stuck to a railing with almost no metal under it, the "ground plane" gets smaller, the feed impedance changes, and the pattern gets lumpy. The antenna did not change length, but its other half got worse.

Radials: building an artificial ground plane

On HF, we usually cannot get a neat metal sheet under a vertical, so we fake it with radials. Each radial wire shares current with its neighbors and gradually approximates a solid surface. The more radials you add, and the better they contact the soil, the closer you get to that "infinite" ground plane behavior.

Buried radials work by forming a low loss transition between the base of the antenna and the soil. Elevated radials are tuned more like actual elements. For a quarter wave vertical mounted a few feet above ground with elevated radials, each radial is cut to roughly a quarter wave and tuned like a little dipole half. In that case, two to four radials can perform nearly as well as dozens on the ground, because they are in the near field and have less contact with lossy earth.

Counterpoise: the emergency stand in for a real ground

A counterpoise is usually a single wire, or a small group of wires, used to provide a return path when a real ground or full radial field is not practical. Classic examples are balcony antennas, portable end fed wires, and magnetic loop matchboxes sitting in a window. The counterpoise gives the antenna system something to push against so the feed line does not have to do all the work.

Because a counterpoise is often small compared to a full radial field, it tends to be more reactive and touchy. Length matters a lot. A counterpoise cut to about a quarter wave can make tuning easy and keep RF off the coax. A random length can land on a resonance that dumps current into the shack. Small adjustments, moving the wire, or adding a choke can make a dramatic difference.

Soil, height, and frequency: the quiet troublemakers

Real ground under an antenna is not a perfect conductor. It has resistance and reactance that change with moisture, salt content, and what is buried under your yard. A vertical over salty wet sand will usually beat the same vertical stuck in rocky dry dirt with no radials. That is why two hams with the same antenna model can report very different results.

Height above ground also changes the game. A 2 meter quarter wave on a car roof is many wavelengths above the soil and mostly sees the metal body. A 40 meter vertical with radials is only part of a wavelength tall and interacts heavily with the earth under the radial field. At HF, spending time on radials usually buys you more than tweaking the last inch on the radiator.

What happens on the air when the RF ground is wrong

From the operator seat, a bad ground plane or counterpoise shows up as stubborn SWR, strange tuning curves, or patterns that just do not match the datasheet. You might notice the antenna tunes sharply on one band, but falls apart on another. Or it tunes fine, but reports on the air are consistently weak compared to what you expect from your power level and height.

In more severe cases, RF returns through the coax and into the shack. Symptoms include hot mic cases, tingling when you touch the rig, distorted audio, or USB interfaces that randomly disconnect. These are all signs that the antenna system is using the station as part of the RF return path. Better radials, a proper counterpoise, and good common mode chokes usually fix the problem.

Practical tips: matching the "ground" to the antenna

Once you can see the RF return path in your head, choosing the right solution gets easier. You do not need a perfect radial field on every antenna, but you should always make sure there is a clear, intentional RF path back to the feed point that does not run through your rig and computer. Here are some simple starting points.

- For ground mounted HF verticals, aim for at least 16 quarter wave radials and add more as your budget and yard allow.

- For balcony or portable end fed antennas, add a quarter wave counterpoise and a coax choke just outside the matchbox.

- For mobile whips, maximize metal under the antenna and keep mounts and paint clean so the whole vehicle body becomes the ground plane.

FAQ: common "ground" questions from new hams

If you are just getting started, it is very easy to mix up RF ground, station safety ground, and whatever the manual means when it says "attach ground wire here." These quick answers should help untangle the worst of the confusion.

Is a ground rod the same as radials?

No. A single ground rod is mainly about safety and lightning, not RF efficiency. It has very little surface area at RF. Radials spread that contact out over many wavelengths and greatly reduce loss. You still want a ground rod for station safety, but it does not replace a proper radial system under a vertical antenna.

Can I use my coax shield as the counterpoise?

Technically, yes, and many end fed antennas do exactly that when you do not give them anything better. The problem is that the coax then radiates, which drags RF into the shack and messes with your pattern. A dedicated counterpoise wire plus a choke on the feed line keeps most of the RF outside where it belongs.

Where should I start if I am overwhelmed?

If you are totally new, start with something forgiving like a simple dipole from the Getting Started section and then move into verticals after that. When you are ready for more, browse the antenna articles and put your new understanding of ground planes, radials, and counterpoises to work on a real build.

Putting "ground" to work in your own station

Ground planes, radials, and counterpoises all exist for the same reason: your antenna needs a solid RF return path if you want it to play well. Once you can see that invisible half of the system, it gets much easier to understand why some antennas shine and others disappoint, even when the marketing photos look identical.

- Verticals want a big, low loss return path, either through a good radial field or a solid ground plane.

- End fed wires and balcony antennas depend heavily on a well sized counterpoise and proper choking of the coax.

- Mobile setups live or die based on how much real metal you put under the whip and how good the bonding is.

If you are ready to go deeper, pair this article with the other pieces in the Getting Started and SDR sections, then start experimenting at your own QTH. A few extra wires in the yard can easily be worth more than another hundred dollars of hardware.