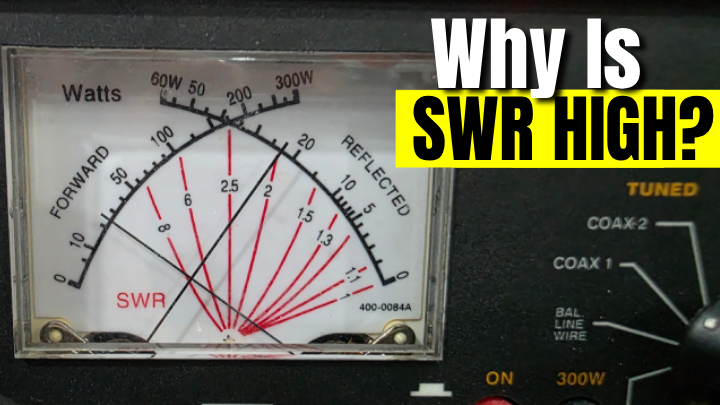

Your rig is warmed up, you hit the tuner button, and the SWR meter slams into the red. Now you are wondering if you are about to fry something. High SWR is one of the most common problems new hams and returning operators run into, and it can be confusing because the meter only tells you "good" or "bad" without saying why. This guide walks through the ten most common reasons your SWR is high and what you can realistically do to fix each one without expensive gear.

📌 TL;DR - Fixing high SWR on your station

- Core idea: High SWR almost always comes from an antenna, feedline, or connection problem, not from the radio itself.

- Why it matters: Poor SWR wastes power as heat, stresses finals, and hides bigger issues in your station layout.

- Key benefit: Systematically checking feedline, connectors, antenna dimensions, and surroundings usually brings SWR into a safe range quickly.

- Who it is for: New and intermediate hams setting up HF or VHF/UHF antennas at home, in the field, or in vehicles.

Before you reach for the credit card or start randomly chopping coax, slow down and treat SWR like any other troubleshooting job. You are chasing an impedance mismatch somewhere between the radio and the antenna. That mismatch may be as simple as a loose PL-259, a too-short whip, or a vertical parked next to a metal gutter. With a methodical approach, you can usually bring high SWR down to something your rig is perfectly happy with.

If you are brand new to HF or VHF, it might help to skim the Getting Started guide first so the vocabulary feels familiar. You do not need an analyzer or a fancy tuner to find most of these issues, but having at least a basic SWR meter or the built in meter in your rig is essential.

10 most common causes of high SWR (and how to fix them)

- Antenna is too long or too short for the band. A 40 meter dipole used on 20 without a tuner will show high SWR. Even on a single band, a few inches off can move resonance far enough that your favorite frequency looks bad. Fix: Measure the antenna, compare to a basic formula (468 / MHz for a dipole is a good start), and trim or lengthen in small steps while watching SWR.

- Wrong band or frequency. It happens more than people admit. The radio is still on 17 meters, but you are trying to use a 20 meter-only antenna, or you are way off the design frequency. Fix: Confirm band, mode, and frequency, then recheck SWR before touching hardware.

- Bad or waterlogged coax. Old RG-58 that has been in the sun for ten years, crushed feedline under a door, or a run with water in it will all raise SWR and losses. Fix: Swap in a short known-good jumper from the radio to an antenna, or test your existing coax with a dummy load at the far end.

- Poorly installed connectors. Cold solder joints on PL-259s, stray braid touching the center pin, or loose adapters can make SWR jump all over. Fix: Inspect and re-solder connectors, tighten everything by hand, then give a gentle wiggle test while watching the meter.

- Antenna too close to metal or the house. Gutters, aluminum siding, metal roofs, and even rebar in concrete can detune an antenna or pull the pattern in weird directions. Fix: Move the antenna farther from buildings and large metal objects, or higher above ground, and recheck SWR.

- Poor ground or missing counterpoise. Vertical HF antennas and mobile whips rely on a decent ground system. Without it, the feedline and radio chassis try to become part of the antenna, and SWR shoots up. Fix: Add or improve radials, bonding, and counterpoise wires. Check that ground straps are short and solid.

- Damaged traps, coils, or loading components. Multiband verticals and loaded whips use traps and coils that can crack, burn, or corrode. Fix: Inspect traps and coils for discoloration, cracks, or loose hardware. If SWR is terrible on just one band, suspect the trap for that band.

- Common mode current on the feedline. When the antenna and feedline are not balanced, RF can ride back on the outside of the coax, giving strange SWR readings that change when you move the cable. Fix: Add a 1:1 choke balun near the feedpoint or a few turns of coax on a ferrite core where it enters the shack.

- Misleading tuner hiding a bad match. An internal tuner can make the meter on the rig look great while the antenna system is actually terrible at the feedpoint. Fix: Bypass the tuner and measure SWR "raw" at the rig, then again with a meter or analyzer at the antenna end of the feedline if possible.

- Faulty or miscalibrated SWR meter. The tool can be the problem. Cheap meters, wrong power range, or incorrect forward/reflected calibration can all lie to you. Fix: Cross check with another meter or with a dummy load you know is close to 50 ohms.

What SWR numbers actually mean at the radio

There is a lot of superstition around SWR. Many operators treat anything above 1.5:1 like it is deadly, but most modern rigs are perfectly happy up to 2:1 or even 3:1 for short duty cycles. The real issue is how much power you are losing in the feedline and whether the radio is forced to fold back its output to protect itself.

Safe SWR ranges for most ham stations

| Metric |

Value |

Why It Matters |

| SWR 1.0:1 to 1.5:1 |

Excellent match |

Almost all of your power reaches the antenna, and most radios will show full rated output. |

| SWR 1.5:1 to 3.0:1 |

Usable but not ideal |

Some power is reflected, and many rigs start to reduce output. Above 3:1 you should fix the antenna, not just use a tuner. |

Quick checklist to troubleshoot high SWR

If your SWR suddenly went high, or a new antenna will not tune, use this simple checklist before you start making big changes. Work from the radio toward the antenna, fixing one thing at a time. That way you know what actually solved the problem and you avoid creating three new issues while chasing one.

- Step 1: Bypass any tuner, set the radio to low power on a clear frequency in the middle of the band, and confirm the meter is not pegged by testing into a known good dummy load.

- Step 2: Check every connector and jumper between the rig and the antenna feedpoint. Tighten, inspect for shorts, and substitute a short known-good coax jumper where possible.

- Step 3: Verify the antenna length, mounting height, and distance from nearby metal. Make small adjustments and watch which direction the SWR moves so you are tuning instead of guessing.

High SWR vs low SWR: what actually changes at the shack

On paper, SWR is a clean math problem about impedance and reflected power. At the station, it feels more like a personality trait. Low SWR usually means your antenna system is close to 50 ohms at the feedpoint, your feedline losses are manageable, and the radio is not being forced into protection mode. High SWR means something is mismatched, but how that shows up depends on your gear and your operating style.

- At low SWR, the rig runs cool, the tuner hardly works, and power output is stable from band to band.

- At moderate SWR, the radio may quietly reduce power a bit, but you will still make plenty of contacts, especially on HF where band conditions dominate.

- At very high SWR, the rig may cut power sharply or refuse to transmit, coax and connectors can heat up, and you risk damage during long key-down transmissions.

How high SWR steals power and stresses equipment

Think of high SWR as a feedback loop. Power leaves the radio, hits a mismatch, and part of it comes back. The radio sees that reflected power, senses the high voltage standing wave on the line, and pulls back its output to protect the finals. You are paying for RF that becomes heat in the feedline and antenna system instead of useful radiation.

On short coax runs at HF, a 2:1 or even 3:1 SWR will not melt anything, but the losses add up when you run digital modes, long key-down transmissions, or higher power. On VHF and UHF, where feedline losses are higher to start with, a bad match can wipe out most of your signal before it ever reaches the antenna. This is why good feedline and connectors are just as important as the antenna itself.

Practical tips to keep SWR under control

You do not need lab gear to get your SWR under control. A bit of planning and some simple habits go a long way. These tips apply whether you are building your first attic dipole, a portable field antenna, or a mobile setup on a truck.

- Plan your antenna first, then the feedline. Keep coax runs as short as is reasonable and use decent quality cable instead of the cheapest thin stuff you can find.

- Document your measurements. Write down antenna lengths, feedline types, and SWR readings by band so you can spot when something changes months later.

- Add RF chokes where they make sense. A few turns of coax through a ferrite core at the feedpoint or where the coax enters the shack can clean up common mode issues before they show up on the meter.

Real-world examples of fixing high SWR

A typical first HF station might start with a simple 40 meter dipole in the backyard. The operator cuts the wire to a chart, hoists it between two trees, and sees 3:1 SWR on their favorite frequency. By lowering the antenna, trimming each leg a few inches at a time, and getting it up to a more consistent height, the SWR drops under 1.5:1 and the tuner barely needs to work.

Another common scenario is a VHF/UHF mobile whip that shows terrible SWR after winter. The coax was fine, but the mount lost its ground connection due to corrosion on the vehicle body. Cleaning the contact area, tightening the hardware, and adding a short bonding strap between body panels brought SWR back under 1.5:1 without touching the whip. If you enjoy this kind of problem solving, you will probably like some of the antenna projects over on the Antennas section and project pages.

FAQ: common questions about high SWR

Is a 2:1 SWR bad for my radio?

For most modern solid state rigs, 2:1 SWR is not a big deal. Many radios are designed to handle up to 3:1 without damage and will simply reduce power a bit as protection. You should still aim for a better match if you can, but if you are stuck at 2:1 on a band or two, do not let that stop you from getting on the air.

Do I need an antenna analyzer to fix high SWR?

An analyzer makes life easier, especially when you are chasing multiple problems at once, but you can do a lot with just the radio's SWR meter and a dummy load. Use the dummy load to prove the radio and meter are healthy. Then move out toward the antenna, changing only one thing at a time. If you eventually add an analyzer, it will speed things up, but it is not a requirement on day one.

Why is my SWR good on one band and terrible on another?

Multiband antennas are always a compromise. A trapped vertical, off-center-fed dipole, or fan dipole may look great on one band and pretty ugly on another. Sometimes that is by design, sometimes it means one element is the wrong length or a trap is failing. Focus first on the band you care about most, get that one right, then see how the others look before you start chasing every bump in the curve.

Can SWR ever be too low?

If your meter shows 1:1 SWR everywhere, that usually means the meter is lying or a tuner is masking the real value. A perfect match across all bands is not realistic for real antennas. If you see "perfect" SWR all the time, double check that you are measuring with tuners bypassed and meters configured correctly.

Bringing your SWR back into the safe zone

High SWR is not a personal failure or a reason to box up your radio. It is just your station telling you that something in the chain from rig to antenna needs attention. Once you understand the usual suspects, the meter stops being scary and becomes a useful tool.

- Work methodically from the radio out to the antenna, checking tuners, feedline, connectors, and grounding as you go.

- Focus on getting a reasonably low SWR with a solid, safe installation instead of chasing a perfect 1.0:1 number at all costs.

- Use what you learn here to improve future builds, whether that is a stealth attic antenna or a more serious HF setup.

If you are ready to go deeper, check out the other pieces in the Getting Started series and the antenna articles so your next project starts with an SWR meter that behaves itself from day one.