Hearing your own signal bounced through the International Space Station is one of those

ham radio moments you never really forget. The good news is that you do not need a

monster station or an engineering degree to do it. If you have a Technician license,

a dual band VHF/UHF radio, and are willing to learn how passes work, you are already

most of the way there.

If you are brand new to the hobby, start with the basics in the

Getting Started section and then come back to this

guide when you have a callsign.

📌 TL;DR - How to reach the ISS with ham radio

- Core idea: Use a VHF/UHF ham radio to work the ISS crossband repeater or packet digipeater during overhead passes.

- Why it matters: It is a unique, very reachable satellite contact that shows what your station can really do.

- Key benefit: You can do it with modest gear: a dual band radio, a simple antenna, and good pass planning.

- Who it's for: Licensed hams who are comfortable on VHF FM and want to move into satellites and space contacts.

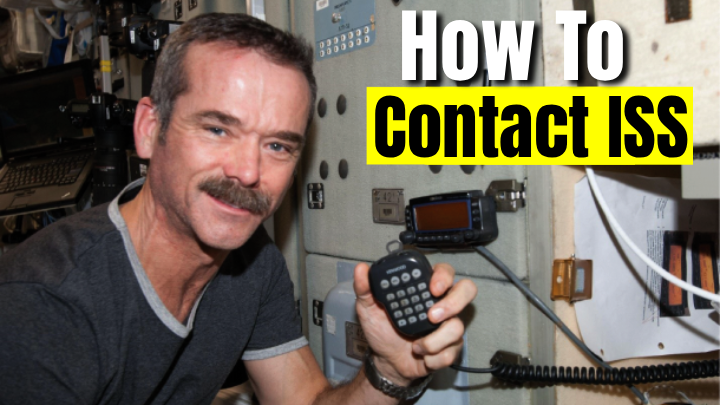

Ham radio on the ISS lives under the ARISS program (Amateur Radio on the International

Space Station). Sometimes the crew gets on for voice contacts, sometimes it is running

FM slow scan TV, and quite often there is an APRS style packet digipeater or an FM

crossband repeater you can work like any other satellite. All of these sound a little

different in the headphones, but the basic operating approach is the same.

In this article we will focus on the things you can do any normal day: hearing the

downlink, working the crossband repeater, and using the packet digipeater. Scheduled

ARISS school contacts are a different animal with a lot of coordination behind the

scenes, but the same radio principles apply. Once you understand passes, Doppler,

polarization, and how to time your call, the ISS becomes just another (very loud)

satellite in your logbook.

What talking to the ISS really looks like

When most people say they "worked the ISS," they did not have a long ragchew with an

astronaut. What actually happens in day to day operation is usually one of three things:

you copy the FM voice downlink when the crew happens to be on, you pass short messages

through the packet digipeater, or you work other hams through the FM crossband

repeater. Each of these is a quick, focused exchange that happens during a 5 to 10

minute satellite pass.

A typical FM repeater QSO might sound like any busy satellite pass: callsigns, grid

squares, maybe a brief signal report, and out. On packet, you are just letting your

APRS frames bounce through and watching the digipeated packets on your screen or on an

online log. The key is timing. You have a small window where the ISS is above your

horizon and the footprint covers you and the other station. Plan that window well and

even a 5 watt handheld and a homebrew Yagi from the

antenna projects section can be enough.

Common ISS amateur radio frequencies

| Metric |

Value |

Why It Matters |

| FM voice / SSTV downlink |

145.800 MHz |

Primary worldwide downlink when the crew is on voice or when SSTV is running. |

| Crossband repeater (uplink / downlink) |

145.990 MHz (CTCSS 67.0) up / 437.800 MHz down |

Turns the ISS into a very strong FM satellite repeater you can work with modest gear. |

Step by step: your first ISS contact

The exact details change as ARISS updates modes, but the general recipe stays the same.

Get your licensing and radio programming sorted, pick a good pass, confirm that you can

hear the downlink, and then make short, well timed calls. Below is the quick version.

We will unpack each piece in more detail afterward.

- Step 1: Confirm your license, program current ISS frequencies (voice, repeater, packet), and practice split operation on your radio.

- Step 2: Use a satellite tracking app to pick a pass with at least 30 degrees elevation and a clear horizon, then get outside with your radio and antenna.

- Step 3: Listen to the downlink first, then make very short calls with your callsign and grid, timed around the strongest part of the pass.

ISS vs regular FM satellites

If you have already played with other FM birds, the ISS will feel familiar and strange

at the same time. The strange part is how loud it is. When the crossband repeater is

active, the downlink can be one of the strongest signals in the whole band. The

familiar part is everything else: Doppler shifts, fast moving passes, and a pileup of

stations all trying to squeeze into a short window of time.

- The ISS is usually louder than small cube satellites, so you can often copy it with a basic handheld and a decent antenna.

- Passes are still short, so exchanges have to be fast, and you should expect heavy congestion on good overhead passes.

- Modes, schedules, and frequencies can change, so you must always check the latest ARISS status before transmitting.

Antennas, power, and what to expect from your station

A lot of people make their first ISS contact with a 5 watt handheld and a better

antenna. The stock rubber duck will sometimes copy the downlink on high elevation

passes, but a simple handheld Yagi or even a tuned quarter wave on a ground plane will

make a night and day difference. If you can already work local repeaters reliably and

have a clean signal, you probably have enough station to at least hear the ISS.

On transmit, 5 to 10 watts is plenty when the pass is overhead. More power helps a little

near the horizon, but pattern and polarization usually matter more. Being able to tilt

and rotate your antenna as the station moves keeps your signal stronger than just

cranking up the watts. If you like experimenting, an SDR on the downlink is very handy

for seeing Doppler and activity across the pass. Check the

SDR section for ideas on that side of the setup.

Practical tips for successful passes

Once the radio is programmed and the antenna is sorted, success mostly comes down to

preparation and discipline on the air. ISS passes reward operators who plan ahead and

operate like adults, not like a HF pileup during a rare DXpedition. A little etiquette

goes a long way when hundreds of people are listening.

- Always verify current ISS frequencies, tones, and modes from a trusted ARISS or satellite tracking source before a pass.

- Record your audio or I/Q during early attempts so you can review what worked and what did not after the pass.

- Keep calls short, avoid doubling, and never try to call crew members outside of announced ARISS events.

ISS ham radio FAQ

Do I need an amateur radio license to contact the ISS?

Yes. You must hold a license that covers the band you plan to transmit on. In the

United States, that means at least a Technician class license for 2 meter and 70

centimeter work. If you are only listening, you can start right away with any scanner

or SDR that covers 145 MHz, but do not press the PTT until you have a callsign.

What is the easiest way for a new ham to work the ISS?

Start by listening to a few passes on 145.800 MHz and, when active, the packet

digipeater. Once you can reliably hear the station, move up to trying a single,

well timed call through the crossband repeater. Treat it like a DX contact: give your

callsign and grid, listen, and then get out of the way if someone comes back to you.

Can I just call the astronauts whenever the ISS is overhead?

Direct voice contacts with the crew happen only during scheduled ARISS school and

special event contacts. The rest of the time, think of the ISS as a shared satellite

resource. Use it for ham to ham contacts and experiments, follow the published

guidelines, and give the crew a break unless you are part of an organized event.

Is contacting the ISS safe for my radio and antenna?

Absolutely, as long as your station is built and operated within normal amateur radio

rules. You are using standard VHF and UHF power levels and antennas. The main safety

concerns are the same as any other VHF station: RF exposure near high gain antennas

and basic tower or ladder safety if you are installing hardware on a roof or mast.

Ready to put the ISS in your log?

Contacting the International Space Station is one of those bucket list QSOs that is

far more reachable than it looks. With a modest VHF/UHF station, current frequency

info, and a little practice tracking passes, you can hear your own signal relayed

from orbit and trade quick exchanges with stations hundreds of miles away.

- You do not need a big station; a dual band handheld and a simple directional antenna can be enough on good passes.

- Success depends more on pass prediction, timing, and clean operating than on raw power.

- Following ARISS mode changes and on air etiquette keeps the ISS usable and fun for everyone.

Program the ISS memories into your radio tonight, pick a promising pass, and see if

you can hear orbiting hardware respond to your backyard signal. Once you have that

first successful contact, the rest of the satellite world opens up quickly.