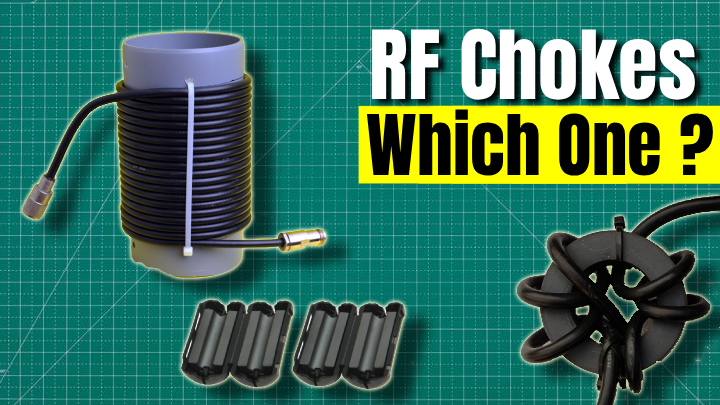

Walk into any hamfest and you will see three completely different approaches to RF chokes. Some hams coil up 10 feet of RG-8X and call it done. Others thread coax through stacks of ferrite toroids. A few swear by commercial sleeve chokes that cost as much as the coax itself. They all claim to kill common-mode current, but which one actually works? More importantly, which one works on your frequency? If your HF antenna works but the shack bites you, patterns look weird, or audio gets wonky when you key up, there is a good chance your coax feedline is part of the antenna. RF chokes are how we fix that mess.

📌 TL;DR — Picking the right RF choke for your feedline

- Core idea: Different choke types excel at different frequencies with different tradeoffs in cost, power handling, and bandwidth.

- Why it matters: The wrong choke can be worse than no choke. It might work on 20m but be useless on 40m, or saturate at high power.

- Key benefit: Understanding the pros and cons of each type helps you pick the right solution instead of guessing.

- Who it's for: Anyone dealing with RF in the shack, TVI, distorted antenna patterns, or trying to make QRP contacts on noisy bands.

All three choke styles try to do the same thing: raise the impedance to common-mode currents on the outside of the coax shield. The higher that impedance at the problem frequency, the less RF flows down the outside of your feedline. Where they differ is in how much choking impedance you get, over what frequency range, how much power they can handle, and how much of a pain they are to build and mount.

What common mode current actually does and why you should care

Coax is supposed to carry RF as a balanced differential signal. Equal and opposite currents flow on the center conductor and the inside of the shield. The outside of the shield should have zero RF current. When that breaks down, you get common-mode current flowing on the outside of the coax braid. That outer surface radiates and receives just like any other piece of wire in your station.

Common-mode current causes real problems. Your antenna pattern gets distorted because the feedline is now part of the radiating system. You get RF in the shack on microphone cables, USB leads, and anything else connected to ground. Your receive noise floor goes up because the feedline is picking up every bit of local RFI. On some bands, you might not be able to transmit at all without tripping breakers or resetting the computer.

The goal of an RF choke is simple: create a very high impedance in series with the common-mode path. If you can push that impedance above 5000 ohms at your operating frequency, most of the common-mode current stops flowing. Get it above 10,000 ohms and you are in very good shape. Below 1000 ohms and you might as well not have a choke at all.

Choking impedance targets and typical performance

| Choke Type |

Typical Impedance |

Frequency Coverage |

Power Handling |

| Coiled coax (8 turns, 6" diameter) |

2-8 kΩ at resonance |

Narrow (1-2 HF bands) |

Unlimited (air core) |

| Ferrite beads (10x Mix 31) |

3-10 kΩ across HF |

Broad (1-30 MHz) |

100-500W depending on beads |

| Ferrite toroids (5 turns on FT240-31) |

5-15 kΩ across HF |

Broad (1-30 MHz) |

500W+ with proper cores |

| Sleeve choke (quarter-wave stub) |

Very high at design frequency |

Narrow (single band) |

Unlimited |

Coiled coax chokes: the air core approach

A coiled coax choke is just a loop of feedline wound into a specific diameter and number of turns. This creates an air-core inductor on the outside of the coax shield. At some frequency, that inductance resonates and the impedance spikes. If you hit that resonance on your operating band, the choke works. Miss it and you might as well have left the coax straight.

The classic recipe is 8 to 10 turns of coax wound on a 6 to 8 inch diameter form. This usually resonates somewhere in the 20 to 40 meter range. Tighter coils with fewer turns push the resonance higher in frequency. Larger diameter coils with more turns push it lower. The problem is that this resonance is sharp. A coiled coax choke that works great on 20 meters might be almost useless on 17 meters.

Coiled coax has two big advantages. First, it costs nothing. You already have coax, and you just need enough extra length to make the coil. Second, it can handle unlimited power because there is no ferrite to saturate. If you are running a kilowatt or more and operating mostly on one band, coiled coax is hard to beat.

The downsides are equally clear. It only works well on one or maybe two nearby bands. It takes up space and can be heavy if you are using thick coax like LMR-400. The coil needs to be secured so it does not unwind, and it should be kept away from metal objects that will shift the resonance. For multi-band operation, coiled coax is usually more trouble than it is worth.

How to build a coiled coax choke that actually works

If you decide to go this route, do not guess. Use a proven design for your target frequency. For lower HF bands like 40 and 80 meters, wind 8 to 10 turns on a 6 to 8 inch diameter form. For 20 meters and up, you can tighten the coil or reduce the diameter slightly. Use zip ties or tape to hold the turns in place, but do not cinch them so tight that you deform the coax.

Mount the coil at the antenna feedpoint if possible. This stops the common-mode current before it gets onto the feedline. If you mount it near the radio, you have already let RF run the length of the feedline, and it may couple into your station wiring before it ever hits the choke.

The biggest mistake people make with coiled coax is assuming more turns is always better. Past a certain point, you are just making the coil heavier and bulkier without gaining much choking impedance. Stick to proven recipes unless you have an antenna analyzer and are willing to measure the actual impedance at your frequency.

Ferrite bead and toroid chokes: the most versatile option

Ferrite chokes use lossy magnetic material to create both inductive reactance and resistance. This combination gives you high impedance over a much broader frequency range than coiled coax. A well-designed ferrite choke can maintain 5 to 10 kΩ of choking impedance from 1.8 MHz all the way up to 30 MHz. That makes ferrite the go-to choice for multi-band antennas and serious RFI problems.

Ferrite comes in different mixes, and the mix determines which frequencies get choked the hardest. Mix 31 is the most common choice for HF. It gives strong performance from about 1 MHz to 300 MHz, with peak effectiveness in the HF ham bands. Mix 43 works well on the lower HF bands and handles more power before saturating. Mix 61 is better suited for VHF and UHF. Mix 73 is used mostly for EMI suppression below 10 MHz.

You can use ferrite in two ways. Clamp-on beads slip over the coax and are held in place with tape or zip ties. They are easy to install but you usually need 8 to 12 beads stacked together to get enough choking impedance. Threading coax through ferrite toroids is more work, but each pass through the core gives you more impedance. Five or six turns of coax through a large toroid like an FT240-31 can give you very high choking impedance across the entire HF spectrum.

Ferrite chokes have two main limitations. First, they can saturate at very high power levels. Once the ferrite saturates, the choking impedance drops and the choke stops working. For most hams running 100 watts or less, this is not an issue. If you are running legal limit power, you need to use larger cores or multiple cores in parallel to avoid saturation. Second, ferrite is more expensive than coiled coax. A stack of quality ferrite beads or a few big toroids can easily cost $40 to $60. That is not outrageous, but it is real money compared to free coiled coax.

Building a ferrite choke the right way

If you are going to invest in ferrite, do it right. For clamp-on beads, use at least 8 to 10 beads of a decent size. Small beads do almost nothing. Larger beads like the FB-31-5621 or similar give you more bang for the buck. Stack them close together and secure them with electrical tape or heat shrink.

For toroid chokes, wind 4 to 6 turns of coax through the core. More turns give more impedance, but past a certain point you run into diminishing returns and it gets hard to fit more coax through the hole. Make sure the coax is not kinked or stressed where it passes through the toroid. If you are building a permanent installation, consider weatherproofing the assembly with heat shrink or a plastic enclosure.

One important note: do not assume all ferrite is the same. Cheap ferrite from unknown sources may not have the permeability or loss characteristics you need. Stick with known good sources like Fair-Rite, Amidon, or similar suppliers who actually publish specs for their materials. If you want to dive deeper into ferrite mix selection, check out the article on ferrite mix types for more detail on when to use Mix 31 versus Mix 43 or other options.

Sleeve chokes: the tidy permanent solution

A sleeve choke is a metal tube or conductive sleeve placed over the coax to create a quarter-wave stub. At the design frequency, this stub appears as a very high impedance and blocks common-mode current. Sleeve chokes are sometimes called bazooka baluns because early commercial versions looked like small bazookas mounted on the coax.

The advantage of a sleeve choke is that it can handle unlimited power and it is very effective at the design frequency. Build a sleeve choke for 20 meters and it will work extremely well on 20 meters. The downside is that it is narrowband. Move to 17 meters and the impedance drops dramatically. If you operate multiple bands, you need multiple sleeve chokes or you need to pick a different approach.

Sleeve chokes are most common in commercial antenna designs and in high-power broadcast applications where single-band operation is the norm. For multi-band ham use, they are usually more hassle than they are worth unless you are willing to build a separate choke for each band. That said, if you have a dedicated 20 meter Yagi and want a bulletproof choke that will never saturate and never need maintenance, a properly built sleeve choke is hard to beat.

Building a sleeve choke for a specific band

To build a sleeve choke, you need a conductive tube slightly larger than the coax outer diameter. Copper pipe from the hardware store works fine. Cut the pipe to a quarter wavelength at your target frequency, accounting for the velocity factor of the dielectric around the coax. Mount the sleeve so it surrounds the coax but does not touch it except at the grounding point.

The tricky part is tuning. A sleeve choke needs to be electrically connected to the coax shield at one end and open at the other. Getting the length exactly right takes some trial and error unless you have an antenna analyzer to measure the impedance. Once it is tuned, though, it stays tuned and requires no maintenance.

Most hams skip the DIY route and just buy a commercial sleeve choke or common-mode filter if they want this style. The commercial units are weatherproof, have known specs, and come with mounting hardware. If you are building a permanent station and want something that just works, this is a reasonable path.

How to choose the right RF choke for your station

The best choke for your station depends on what bands you operate, how much power you run, whether you need a portable solution or a permanent one, and how much you want to spend. Here is a practical decision framework that cuts through the noise.

If you operate mostly on one HF band and run high power, coiled coax is the easiest and cheapest solution. Wind the coil to the right diameter and turns count for your band, mount it at the feedpoint, and you are done. This works great for single-band Yagis, vertical antennas on one band, or any antenna where you know exactly what frequency you will be using.

If you operate multiple bands and run moderate power, ferrite chokes are almost always the best choice. A stack of Mix 31 beads or a few turns through a large Mix 31 toroid will cover you from 160 meters through 6 meters with high choking impedance. This is the default answer for multi-band dipoles, off-center-fed dipoles, end-fed antennas, and vertical antennas used across multiple bands.

If you need a permanent, weatherproof, hands-off solution and only operate one or two bands, consider a commercial sleeve choke or common-mode filter. These are more expensive but they are built to last and come with actual specs instead of guesses. For a permanent tower installation or a fixed directional antenna, this can be worth the extra cost.

Where to place your RF choke

Location matters almost as much as choke type. The best place for an RF choke is at the antenna feedpoint. This stops common-mode current before it gets onto the feedline. If you are building or reworking an antenna, plan for a choke at the feedpoint from the start.

If you cannot put a choke at the feedpoint, the next best location is where the coax enters the shack. This at least keeps RF out of your operating position even if it does not fix the antenna pattern. Some stations need chokes in both places, especially if RFI is severe.

One mistake to avoid: do not put a choke right at the output of a tuner if the tuner is trying to match a severely mismatched antenna. High SWR on the coax side of the choke can cause voltage breakdown or heating in the ferrite. In that case, move the choke closer to the antenna or fix the antenna mismatch first.

Real-world measurements and what actually works

In theory, a well-designed ferrite choke almost always wins. In practice, a mediocre ferrite choke is still usually better than a poorly executed coiled coax choke. The difference comes down to whether you follow a proven recipe or just wing it.

With an antenna analyzer or network analyzer, you can measure the choking impedance of any choke design. What you want to see is at least 5 kΩ of impedance on your operating bands. Below that, the choke is not doing much. Above 10 kΩ, you are in excellent shape. If you do not have an analyzer, follow published designs from sources that do have the test gear. The ARRL Handbook and various application notes from ferrite manufacturers are good starting points.

One common question is whether you can use multiple small chokes instead of one big choke. The answer is yes, but with a catch. Two chokes in series on the same feedline add their impedances together, so two 3 kΩ chokes give you about 6 kΩ total. This is a good way to boost performance if you already have one choke that is not quite enough. Just make sure both chokes are working at your frequency. Two worthless chokes do not add up to one good choke.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

The biggest mistake with RF chokes is assuming one size fits all. A choke that works on 20 meters might do almost nothing on 80 meters. If you operate multiple bands, you need a choke that covers multiple bands. That usually means ferrite with the right mix for HF.

Another common error is using too few ferrite beads. Three or four clamp-on beads look like a lot when you are stacking them on the coax, but they often do not provide enough impedance. Use at least 8 to 10 beads if you are going the clamp-on route. If that seems like too many, switch to toroids and wind multiple turns through a large core.

Some hams worry about power handling and assume ferrite cannot handle high power. This is half true. Ferrite can saturate at high power, but saturation depends on the size of the core, the number of turns, and the RF power level. A single small bead will saturate quickly at 100 watts. A large toroid with multiple turns can handle legal limit power without breaking a sweat. If you are running high power and using ferrite, use big cores and keep the number of turns reasonable.

Finally, do not assume that any choke is better than no choke. A poorly designed choke at the wrong frequency can actually make things worse by creating unexpected resonances or voltage spikes. If you are going to add a choke, make sure it is designed for your frequency and your application. When in doubt, copy a design that has been tested and published by someone with the right test equipment.

Testing whether your choke actually works

If you do not have an antenna analyzer, there are still ways to tell if your choke is doing its job. The simplest test is to key up and feel the coax at various points along the feedline. If the choke is working, the coax on the radio side should stay cool and should not have any RF voltage on it. If you can still feel RF on the coax past the choke, the choke is not working at your frequency.

Another test is to check for RF in the shack. If adding a choke stops hot mics, computer resets, or audio buzz, the choke is doing something useful. If nothing changes, either the choke is not working or your RFI problem is coming from somewhere else.

SWR changes can also give you a clue. If adding a choke at the feedpoint changes your SWR significantly, that tells you the feedline was part of the antenna system. The choke is now forcing the antenna to work on its own without stealing current from the feedline. This is usually a good thing, even if the SWR goes up slightly. A slightly higher SWR on a properly choked antenna is better than a low SWR on an antenna that is using the feedline as a radiator.

Hybrid approaches and when to stack chokes

Sometimes one choke is not enough. If you have severe RFI or you operate across a very wide frequency range, you might need multiple chokes. One approach is to use a coiled coax choke at the feedpoint for your primary band, then add a ferrite choke near the shack entry to cover other bands. This gives you the best of both worlds: narrowband high impedance where you need it most, plus broadband coverage everywhere else.

Another option is to use multiple ferrite chokes in series. This can push your total choking impedance above 20 kΩ, which is overkill for most situations but can be useful if local RFI is extreme. Just make sure you are not creating a mechanical nightmare with too much weight or bulk on the feedline.

For multi-band vertical antennas, some hams use a sleeve choke at the base for one band plus ferrite beads higher up on the coax for other bands. This keeps the installation relatively clean while still providing good common-mode suppression across multiple bands. There is no single right answer here. Experiment and measure until you find what works for your station.

RF choke FAQ

Do I really need an RF choke on my HF antenna feedline?

If you run unbalanced antennas like end-fed half-waves, off-center-fed dipoles, multiband verticals, or anything that uses the coax as part of the return path, yes, an RF choke is almost always worth adding. Even on balanced antennas like center-fed dipoles, a choke at the feedpoint keeps the feedline from becoming part of the antenna. You may not notice a huge change every time, but most stations see lower noise, fewer RF-in-audio problems, and more consistent patterns once common-mode current is under control.

Can I just use a 1:1 balun instead of a dedicated RF choke?

Some 1:1 baluns are current baluns, which are basically ferrite RF chokes packaged as a balun. Those are perfect. Others are voltage baluns that provide impedance transformation but do almost nothing to stop common-mode current. If the manufacturer publishes choking impedance plots, you are good. If they do not say anything about common-mode performance, treat it as suspect and add a real choke. A true current balun with high choking impedance serves both purposes. A voltage balun does not.

How do I know if my choke is saturating at high power?

If your choke gets hot during transmit, it is either dissipating common-mode current as heat or it is saturating. Both are problems. Dissipating current as heat means the choke is working but might be undersized for the power level. Saturation means the choking impedance is dropping and the choke is losing effectiveness. If you are running high power and using ferrite, use larger cores or reduce the number of turns to avoid saturation. Coiled coax and sleeve chokes do not saturate because they do not use ferrite.

Can I use different choke types on different bands?

Absolutely. Some stations use a coiled coax choke optimized for 20 meters because that is where they spend most of their time, then add a small ferrite choke to cover 40 and 80 meters. Others use a primary ferrite choke at the feedpoint and a secondary coiled coax choke at the shack entry. There is no rule that says you have to pick one type and stick with it everywhere. Use what works for each specific situation.

So which RF choke is actually best?

There is no single choke that wins in every situation, but there is usually one that is clearly the best fit for your station. Coiled coax is cheap and effective for single-band high-power work. Ferrite chokes give the highest and most reliable common-mode impedance across multiple bands. Sleeve chokes and commercial units keep the install tidy and weatherproof for permanent installations.

- Use ferrite chokes when you need broadband common-mode control on multiple HF bands and run moderate power.

- Use coiled coax when you operate mostly on one band, run high power, and want the simplest and cheapest solution.

- Use sleeve or commercial chokes when you want a permanent, weatherproof installation with documented specs.

- Use multiple chokes if one is not enough, but make sure each choke is doing something useful at your frequencies.

If you are building or reworking a station right now, treat RF chokes as core parts of the design, not last-minute add-ons. Pair them with efficient antennas from the antenna articles, clean up your station grounding, and you will end up with a station that is quieter, cleaner, and a lot more fun to operate. For more technical details on ferrite selection, the ferrite mix guide and other resources under radio articles can help you fine-tune your choke choices for your specific bands and power levels.